Light in the Citadel

A Room of Stillness

One of Kaveh Golestan’s photographs captures a peaceful moment that stands in its own world. A woman sits quietly on her bed in a tiny room in Shahre No. Light comes in unevenly from a window that may not open. The wallpaper behind her curls like some weary waves from the wall. She glances at Golestan with cool recognition. His camera is lowered. He waits. He’s waiting to meet her there, as she is. In this shared stillness, an unspoken agreement sets in between them. This is the tone that defines his entire portfolio in the district that Tehran wanted to forget.

Golestan spent long periods in Shahre No from 1975 to 1977. He strolled through its alleys, looked into its rooms, and sat with its residents without hurry. He read the reports he had learned about from social workers, studied the district's history, and then came back. His portraits were made after a year and a half of patient presence and what he called “empathetic sensitivity” (Mahlouji, 2016). This was not the frantic passage of a photographer through an outlying space. It could be the slow rhythm of someone making sense of a world from inside it.

© Kaveh Golestan, Prostitute Series, 1975–1977

© Kaveh Golestan, Prostitute Series, 1975–1977

The Neighbourhood at Dusk

Shahre No was on the periphery of Tehran, but it was one of the city’s own deepest rhythms. At dusk, the district was lively with sounds: women gathered behind open doors, conversations buzzed from inside the houses, and radios played softly in the background. A subdued glow from the lamps lit up the narrow alleyways. At the same time, the men entered and exited the area quickly, walking swiftly and avoiding eye contact while constantly looking. The district absorbed their desire and had the women shoulder the burden of shame.

Initially established by a political decree as a segregated red-light district in the early 20th century, Shahre No grew as the city expanded. Following the 1953 coup led by foreign powers, the government sealed the area behind a wall with a single gate (Mahlouji, 2016). It contained small homes, shops, clinics, and hundreds of single rooms. By the 1970s, some fifteen hundred women lived and worked in its periphery (Rashidbeigi, 2015). The rest of Tehran acted as if the district didn’t belong to the city, and depended on what happened inside its walls for that.

Desire, Shame and the Frail Architecture of Survival

Many women living there arrived due to circumstances beyond their control. Some were abandoned, others sold by families in crisis, some came from rural provinces without social protection, and domestic violence or forced marriage. The conditions in the district were harsh. The women lived in single-room households and laboured long hours at home and at the workplace, often with no legal or financial security. They faced daily hardship and the prejudice of a society that relied on their labour yet refused to recognise their humanity.

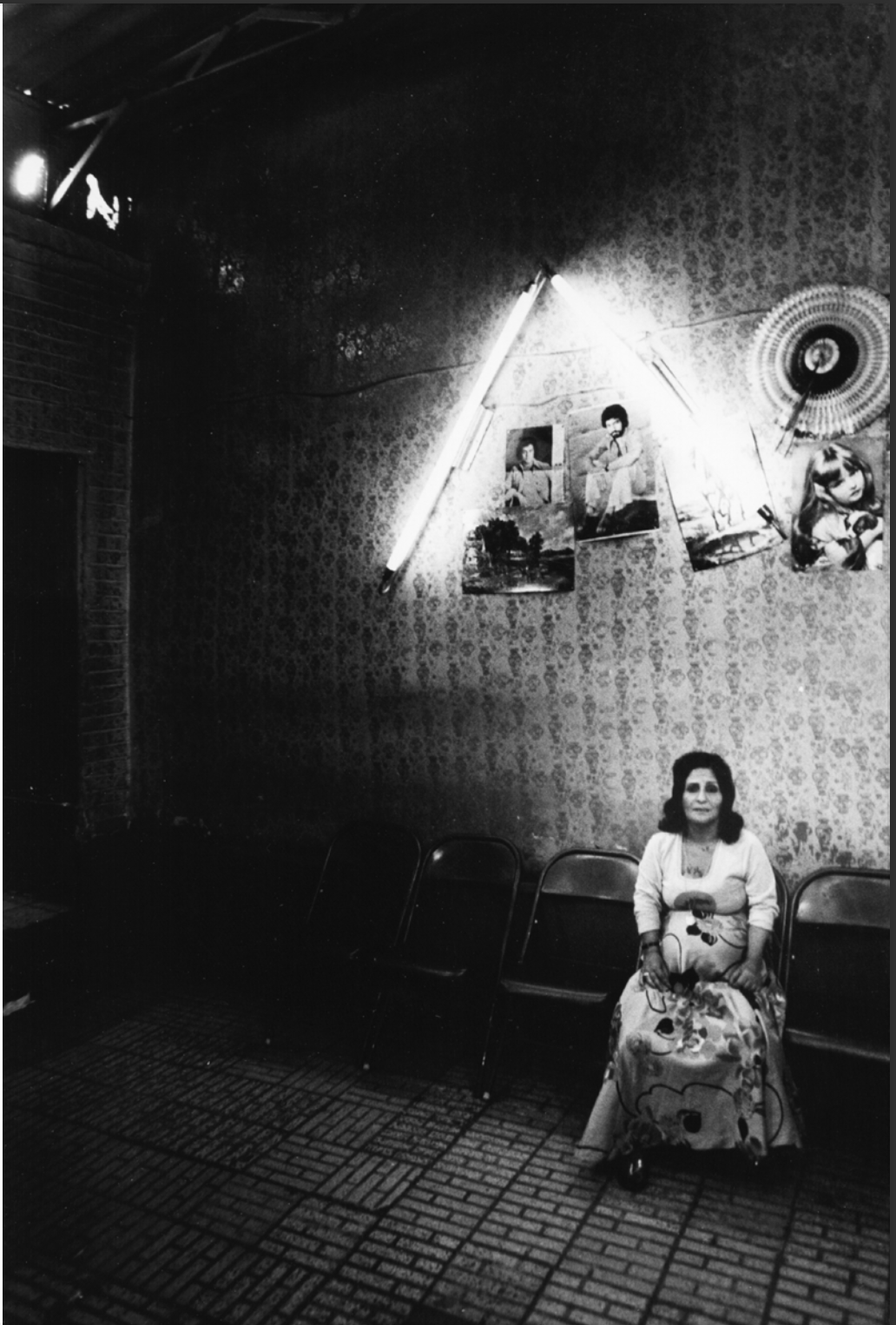

Researchers who have examined the neighbourhood have called the district “a tight beehive of tiny cells,” a structure that fosters social isolation and both physical and psychological distress (Dezhamkhooy and Papoli Yazdi, 2020). The women’s labour was critical to the district's well-being, but their existence was frequently excluded from social membership. Their rooms held a vestige of their world inside. Some hung posters or small religious images on their walls, others decorated their quarters with fabric, photographs, or whatever they found. They were minor instances of self-preservation in a site where survival took precedence over hope.

© Kaveh Golestan, Prostitute Series, 1975–1977

Learning to look through care

That’s where Golestan’s photographs distinguish themselves. He refused to embrace the dominant traditions that for years had depicted Middle Eastern women through exoticism or voyeuristic fantasy. He did not photograph Shahre No as a remote observer; instead, he slowly entered the place to build trust. His eyes remained kind and respectful; he spent years developing and learning relationships around the neighbourhood before he installed a camera. He erased the line between himself and his subjects, letting them dictate the conditions of their encounter. His photographs reflect this through the women looking back, looking forward, looking inward. Their faces are tinged with exhaustion, pride, humour, anger and sometimes relief. The photos are never reduced to symbols; each illustrates people. Golestan believed that photography carried a civic duty, and he used his camera, which the authorities wanted the public to ignore. By publishing three photo essays in the newspaper Ayandegan, he aimed to highlight the living conditions of its residents and foster collective awareness (Mahlouji, 2016). His work became a form of witnessing rather than merely exposing.

© Kaveh Golestan, Prostitute Series, 1975–1977

Presence, and the Absence That Speaks Behind It

Golestan portraits reveal other layers of the figure captured in the frame. The posters hanging beside a cracked wall, a cat on a woman's lap, a fan might lurk next to a chipped mirror sitting in a corner. These are details that reflect the lives lived by the people in the room, but they also capture absence. The absence of security. The absence of recognition. The absence of rights. Absence becomes evidence of the social forces shaping the women’s lives; it shows what the photograph cannot directly state. It reminds us that Shahre No existed because of inequalities that the city was unwilling to face.

Shahre No was a community with its own rhythms. Women formed bonds with each other, established routines, and looked out for one another. They shared food, stories, and sometimes laughter. They found ways to create meaning inside a system that offered them little stability. Their humanity remained intact despite the weight placed on them by their families, the state, and the clients who entered the district each night.

© Kaveh Golestan, Prostitute Series, 1975–1977

Fire, Erasure, and the Politics of Purification

In January 1979, everything changed.

Two days before Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran, a group of armed men set fire to the district. The flames spread rapidly through the wooden structures. Some women died inside their rooms, others fled the fire only to be arrested, and several were executed in the months that followed. The entire district was demolished soon after, and a hospital and a park were built on the land to ensure that no trace of its past remained. The destruction was framed as a moral cleansing during the revolution, but it was also the erasure of a neighbourhood that embodied contradictions the new political order wanted to remove (Amanat, 2017).

Golestan’s portraits are now the last surviving images of many of the women who lived there. They compile an archive to prevent forgetfulness and to preserve, in the name of moral purity, the lives often left unrecorded by official history, ensuring they remain visible. The photographs reveal a social structure built on the management of desire, the enforcement of shame, and the daily struggle for survival.

What It Means to Look Today

Looking at these images today prompts reflection on how we perceive vulnerable people in our era. We live in a world where photographs circulate without context, images travel instantly and continuously, and are consumed without care. This speed can repeat the violence of erasure even when the intention is to document or resist.

Golestan’s method teaches an alternative. It asks for a slower gaze. It reminds us that looking should be grounded in empathy, responsibility, and awareness of the histories that shape the subjects. The politics of intimacy remain central in Iran today. The state continues to regulate women’s bodies, visibility, and autonomy. Shame and control still shape daily life.

In this context, Golestan’s work speaks directly to the present. It reminds us that the forces that confined the women of Shahre No did not disappear with the district. They transformed and reappeared in new forms across different spaces and generations.

Within These Walls

Perhaps the most compelling way to conclude is by returning to a portrait, one of a woman sitting before a wall filled with photographs and fragments. The room is small, yet imbued with traces of lives and moments that came before her. As she rests on soft cushions, her posture is composed and her presence remains steady. When Golestan took this photograph, the district was still alive with its own rhythms. The fire and destruction came later. What endures now is this quiet moment, held in the frame with remarkable care.

The photographs are not trying to speak on behalf of these women. Through this image, she remains visible in a history that attempted to erase the place where she lived. Golestan’s attention turns the act of looking into a form of respect. It reminds us that how we see others shapes what survives. In this final image, presence becomes its own form of memory, asking us to look with the patience the moment deserves.

© Kaveh Golestan, Prostitute Series, 1975–1977