THE ILLUSION OF SOFTNESS

If you follow social media, you’ve likely heard of Kim Kardashian’s latest creation, the hairy tanga. The internet treated it as entertainment, part laughter, part fascination, part disbelief. What started as just a viral moment quickly became a reflection of something much larger.

Beneath the spectacle is a story about how modern consumption shrouds itself in gentleness. The way SKIMS, a brand built on the vocabulary of comfort, has turned the rhetoric of sustainability into a soft, beige promise.

THE RISE OF SOFT CONSUMPTION

SKIMS captures the beat of our era. Its clothing speaks of ease and inclusion, of natural hues and silky textures that can melt into the body. The photographs are calm and convincing; they deliver a message: style can merge with responsibility. The words on its site turn care into an act of beauty: "responsible production", "recyclable packaging", alongside "luminous skin" and "neutral light,".

As with today's fashion industry, sustainability has become a fixture in everyday parlance. What was once a protest now circulates through campaigns and influencer captions. The vocabulary of sustainability has become assimilated into the mainstream, reorganised into marketing practices. Brands no longer have to show any commitment on their part, but they must still sound ethical (McKeown, 2019).

THE PROMISE AND THE PERFORMANCE

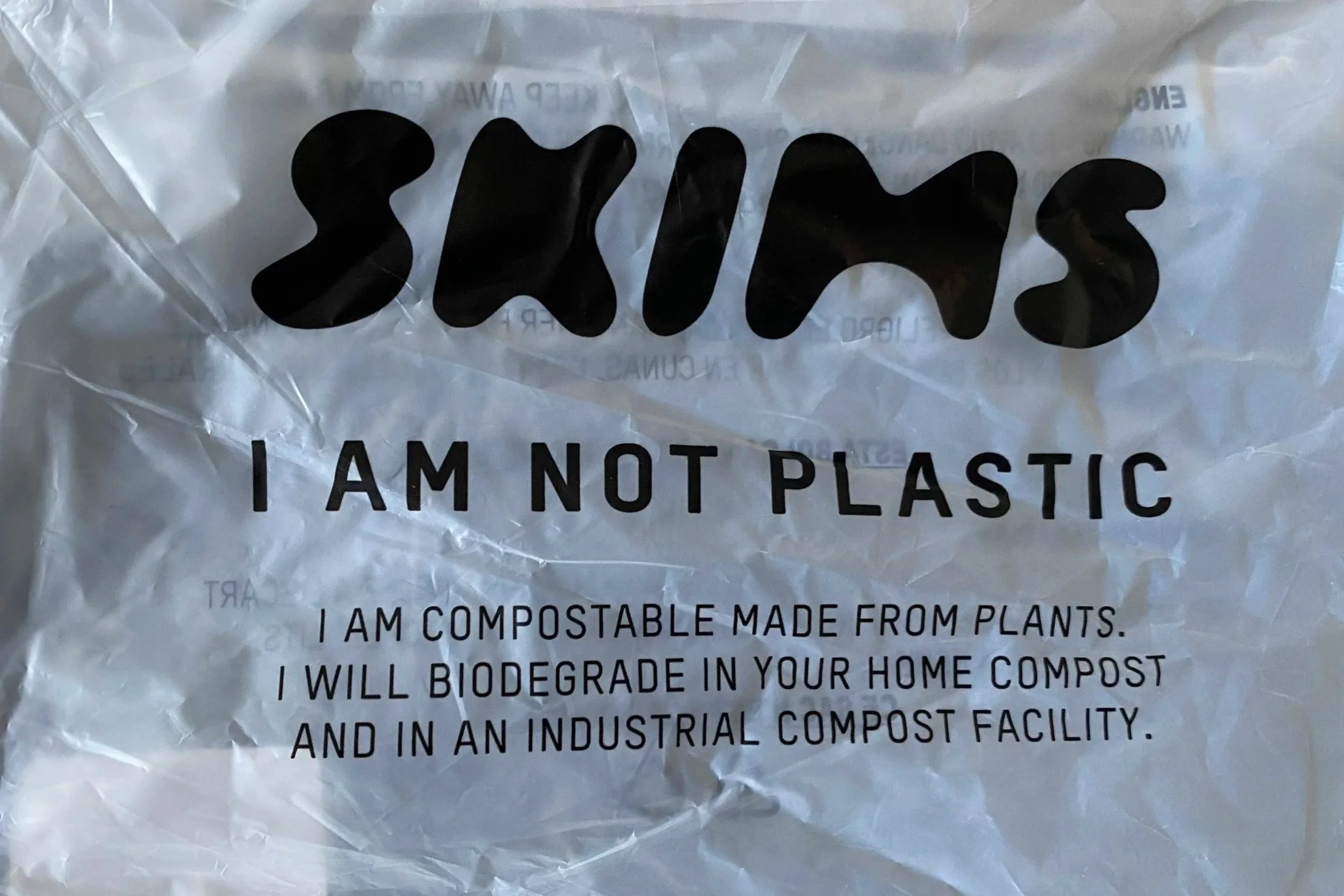

This transformation is well captured in the SKIMS universe. Its widely recognisable packaging, stamped with “I am not plastic,” looked like a sign of new responsibility, as if they were upholding their ethical standards. But an inquiry by the Changing Markets Foundation found that the material was actually made from low-density polyethene, a plastic that cannot biodegrade in home composting. Such labelling, according to the report, is misleading and mendacious, and it also indicates a wider pattern of brands marketing virtue while using the same synthetic materials.

Image source: Greenwash.com, article “To be or not to be plastic?” (2022). © SKIMS.

Research by fashion communication scholars identifies this strategy as greenwashing: the practice of highlighting fragments of progress while concealing the rest (Adamkiewicz et al.). The efficacy of these campaigns often depends more on how they sound rather than what they actually change. The phrases “eco-friendly” or “plant-based” conjure up a sense of calm purity, but very rarely are they really explained what those terms mean. This kind of language makes sense of responsibility, turning even the most basic actions into an integrated brand identity rather than just a production process.

This effect is amplified by celebrity power. Kim Kardashian’s image makes SKIMS feel familiar, inviting people to trust her as they would a friend. That intimacy adds to the brand’s credibility and softens public scrutiny. This charm serves as a kind of smokescreen, making the care story attractive yet an unattainable reality becomes the journey's reality (Chung, 2025).

THE INFLUENCE ECONOMY

Social media has been the new atelier of meaning. Influencers are moulds of conscience, sewing together a performance of ethics and entrepreneurship into content that aims to be respected and admired. This has been termed by Jacobson & Harrison (2022) as content creation calibration, the art of modifying one’s message to fit both ethical concern and commercial ambition. The result is a terrain of sincerity cohabited with self-promotion, where caring itself becomes a lifestyle brand.

However, Gen Z audiences aren’t easily fooled; they navigate this landscape with sharp insight and awareness. Even when it comes to greenwashing, young consumers still engage in it (Haque & Lang 2025). They have an emotional relationship to brands founded on belonging and optimism. Buying from a brand like SKIMS feels like partaking in a shared dream of comfort — a space where identity and ethics seem to overlap.

THE CULTURE OF BEIGE

Beige has become the colour of virtue. The SKIMS palette of neutrals and soft fabrics creates a sense of peace, as if moral clarity could be worn. Here, simplicity signifies sincerity, and silence represents integrity. As the body appears harmonious, the message is balanced, and the conscience remains clean.

But the calm that soothes also hides. When every brand enforces such a nice little word, the language of sustainability becomes decorative. Ethical discourse has now become a ubiquitous, if often empty, narrative in its own right (McKeown, 2019). The consumer readily moves into this rhythm, drawn by narratives of care and by the layered promises of identity, aspiration, comfort, and social recognition.

Fashion theory demonstrates that clothing always says something about us, who we are, and who we aspire to be. The outfit is both a statement and a shield, a way of making oneself seem aware without actually facing the complexity of awareness itself.

THE COST OF ILLUSION

This softness of illusion gives many, including those who make it, a sense of comfort. Kim Kardashian has honed the practice of manipulating the art of providing reassurance to desire. SKIMS makes it easy for people to assume that comfort is itself a kind of activism, that by caring for others, making a gentle face is acting responsibly.

Real sustainability, though, has a different rhythm. It continues in stages, under the guise of transparent supply chains, fair labour and honest communication. It loves endurance over novelty, data over imagery. Real change relies on measurable responsibility and not empty talk (Adamkiewicz et al., 2023).

The viral hairy tanga, both absurd and irresistible, epitomised this paradox. While viewers discussed humour and taste, the greater problem of production and consumption quietly slipped away.

Sometimes the ethics of what we wear can start as small gestures of curiosity. On researching this, I stumbled upon greenwash.com, a site created by the Changing Markets Foundation that catalogues examples of misleading environmental claims. It's one of several new platforms emerging that ask us to consider how morality is shaped by commerce, and how simply having awareness can be an act of care.

-

Adamkiewicz, J., Kochanska, E., Adamkiewicz, I., & Łukasik, R. M. (2023). Greenwashing and the Sustainable Fashion Industry.

Changing Markets Foundation. (2022). Brands Exposed for Misleading and Mendacious Packaging Claims. Available at changingmarkets.org

Changing Markets Foundation. (n.d.). Greenwash.com. Available at greenwash.com

Chung, K. (2025). Marketing in Fast Fashion: Greenwashing and Celebrities as Smokescreens. Technium Social Sciences Journal.

Haque, M. N., & Lang, C. (2025). Unraveling the Green Veil: Investigating the Affective Responses of Generation Z to Fast Fashion Greenwashing. Sustainability, 17(11), 4973.

Jacobson, J., & Harrison, B. (2022). Sustainable Fashion Social Media Influencers and Content Creation Calibration.International Journal of Advertising, 41(1), 150–177.

McKeown, S. (2019). Taking Sustainable Fashion Mainstream: Social Media and the Institutional Environment. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 18(5), 1–15.